On Copacabana Beach.

As a post-doctoral fellow in Rio de Janeiro in 1960, Smale worked on mathematical problems that were to prove of central importance in the emerging field of chaos theory. He had an office at the Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics (IMPA), a newly established research centre in Rio.

After his Brazilian sojourn, Smale took up a professorship at Berkeley. In 1965, President Johnson escalated the Vietnam War, and Smale led some student demonstrations against US military aggression. Politicians took a dim view of his beach-time research: Johnson’s science advisor questioned why taxpayers should support research on the beaches of Rio. Political factors influenced the evaluation and rejection of Smale’s next application for scientific funding.

A Lost Letter Found

Recently, a 1960 letter from MIT Professor Norman Levinson to Smale was found in an archive at IMPA. It concerned research originating with a World War II study of radar by Mary Cartwright and John Littlewood on the behaviour of radio oscillators and revealed an error invalidating Smale’s work. But blunders can be a boon: in correcting the error, Smale was led to a discovery, the horseshoe map, that would foreshadow a scientific revolution.

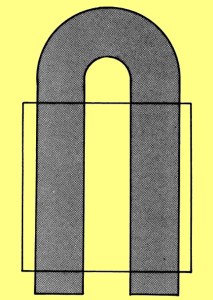

To describe the horseshoe map, think of how a baker stretches and folds dough to mix it well. With this action repeated, nuts and raisins originally clustered in one place will be spread out uniformly in the loaf. Smale showed that the horseshoe map can be represented by a sequence of tosses of a coin, the paradigm of pure chance. His discovery of the horseshoe map had consequences that might be described as chaotic.

The Emergence of Chaos

The recognition of “sensitive dependence to initial conditions” is now an essential starting-point for solving many problems in science. Newton’s laws of motion provided a means to predict the motion of a mechanical system given a starting point, or “initial conditions”. Scientists came to believe that, given precise initial conditions, the behaviour of a physical system up to any future time could be predicted accurately.

In the 1970s, a revolutionary new scientific perspective, the theory of chaos, emerged, that dealt a severe blow to Newtonian determinism: we must deal with unpredictability. Chaos became evident through the deep analysis of the equations underlying Newtonian mechanics. Through mathematics, the inadequacy of Newtonian determinism was revealed.

Chaos was already implicit in the work of Cartwright and Littlewood and, much earlier, in Henri Poincaré’s studies in celestial mechanics, but the world was not ready to accept the counter-intuitive ideas it entailed. Even meteorologist Edward Lorenz’s 1963 paper, Deterministic nonperiodic flow, was not appreciated for a decade after it appeared.

A few months after the discovery of the horseshoe map, Smale made a breakthrough in topology. He proved a key conjecture of Henri Poincaré in dimensions greater than 4. It was for this that he was awarded the Fields Medal in 1966.

Sources

Steve Smale, 1998: Finding a horseshoe on the beaches of Rio, Math. Intelligencer 20 , No. 1, 39 – 44.

Jair Koiller and Indika Rajapakse, 2025: Apropos the Long-Lost Letter from Levinson to Smale, Now Found! Notices Amer. Math. Soc., 72, No. 7, 748 – 754.

Evening Course, UCD

A UCD course on recreational mathematics, “AweSums: the Majesty and Magnificence of Mathematics”, will be presented this autumn by Peter Lynch — registration is now open. For details, see LINK.