Is the universe finite or infinite in extent? This question has been a preoccupation of philosophy for millennia, and scientists continue to grapple with it. Wherever infinity appears, paradox looms up. Given the finite speed of light, an infinite cosmos would have regions forever unknowable to us. But even a finite cosmos presents perplexities: if the universe is bounded, what lies beyond? [TM277 or search for “thatsmaths” at irishtimes.com].

Central to the question of the shape of space is the mathematical concept of curvature. We are all familiar with curves on a flat plane, like gentle or sharp bends in the road. Fitting a circle to a curve, we can express the curvature as the inverse of the circle’s radius: a large radius means a small curvature while a small radius means large curvature. Formula One drivers are keenly aware of this.

The idea of curvature applies also to surfaces. On a flat plane, Euclidean geometry reigns: the angles of every triangle add to two right angles, and the theorem of Pythagoras is valid. But on the spherical Earth, this is no longer true and the geometry is non-Euclidean: a triangle with one corner at the North Pole and two on the Equator has two right angles — possibly three — and the Theorem of Pythagoras no longer holds.

At a fixed point on a surface, the curvature may vary in different directions: think of the summit of a mountain pass, where the land rises to left and right while sloping downward ahead and behind. The great mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss expressed overall curvature in terms of the largest and smallest circles fitting a surface in 3-space. For a sphere, these “kissing circles” have the same radius and the curvature, which is the inverse square of the radius, is everywhere positive. At the mountain pass the curvatures are of opposite signs in the forward and lateral directions, and their product gives the Gaussian curvature, which is negative.

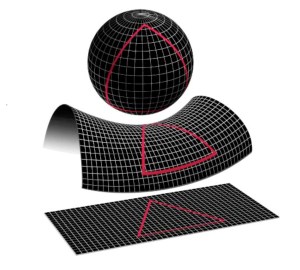

Gauss proved a result that he dubbed his “Remarkable Theorem”. He showed that the curvature of a surface in 3-dimensional space can be determined by measurements within the surface itself. The Gaussian curvature does not change if the surface is bent without stretching; it is intrinsically invariant. The surface of a cylinder has zero curvature, since it can be unrolled onto a flat plane. In contrast, the surface of the spherical Earth can never be mapped without distortion onto a flat plane: there are no perfect maps.

Bernhard Riemann greatly extended Gauss’s work, defining curvature in multi-dimensional spaces. The Riemann curvature tensor plays a central role in Einstein’s general relativity theory. In this theory, the curvature of the universe and its total mass-energy density are linked. Positive curvature, like that on a sphere, implies a finite universe, while zero curvature, as on a flat plane or negative curvature, as on a saddle or pringle-shaped surface, is indicative of a cosmos that is infinite.

The observable universe is a roughly spherical region about 50 billion light-years in diameter, but our understanding is that space extends far beyond this. Recent astronomical observations show that the curvature is very small, suggesting that the universe is either infinite or ineffably immense, so vast that most of its extent will remain forever beyond our reach.

One thought on “The Shape and Size of the Universe: Curvature is Key”

Comments are closed.